Welcome

Welcome"The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time" (British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, 3 August 1914)

The New York Times newspaper; Why Hungary Inspires So Much Fear and Fascination Aug. 7, 2021, By Ross Douthat, Opinion Columnist

For the last few years, Hungary, a country of fewer than 10 million people, has occupied an outsize place in the imagination of American liberals and conservatives. If you think the American right is sliding toward authoritarianism, you cite Viktor Orban's nationalist government as a dark model for the G.O.P. If you think an intolerant progressivism shadows American life, you invoke Orban as a figure who's fighting back. In this running debate, sharpened by the recent Tucker Carlson visit to Budapest, I was struck by an observation from The Atlantic's David Frum, a fierce critic of the right's Orban infatuation. As part of a Twitter thread documenting corruption in Orban's inner circle, Frum wrote: "I visited Hungary in 2016. Again & again, I witnessed a gesture I thought had vanished from Europe forever: people turning their heads to check who was listening before they lent forward to whisper what they had to say. They feared for their jobs, not their lives – but still ..."

This is a useful tweet for thinking about the fears motivating Hungary-watching Americans, left and right. On the one hand, there's the fear that Trumpian populism will someday gain enough power to make its critics fear for their livelihoods. On the other, there's the fear that progressivism already exerts this power in the United States, and that what Frum describes in dire terms, the cautious sotto voce conversation, is an important part of American life right now.

You can document this fear of sharing strong opinions, especially ones that conflict with progressive orthodoxy, by looking at opinion polls. For example, a 2020 survey conducted by the Cato Institute found that 62 percent of Americans felt uncomfortable sharing their views because of the political climate, and "strong liberals" were the only ideological group where the majority felt free to speak "their minds. To the question, "Are you worried about losing your job or missing out on job opportunities if your political opinions became known? highly educated Americans were the most anxious, with 44 percent of respondents with a postgraduate degree and 60 percent of Republicans with a post-grad degree saying yes.

Alternatively, you can document this fear by just keeping up with the ever-lengthening list of people who have had careers derailed for offenses against progressive norms. (Often they are heterodox liberals rather than conservatives, because conservatives are rare in elite institutions and less interesting to ideological enforcers.) Or by observing the climate of denunciation and abasement in various cultural spaces, from academic journals to law schools to the publishing industry. Or just by having everyday conversations in professional-class America: I've experienced more versions of the speak-quietly move – or its "don't share this email" equivalent – in the last few years than I have in my entire prior adult life.

This fear is different from the fear that Frum discerned in Hungary, in the sense that nobody in the United States is afraid of criticizing the government. The censorious trend in America is more organic, encouraged by complex developments in the upper reaches of meritocratic life, and imposed by private corporations and the ideological minders they increasingly employ. If this is left-McCarthyism it lacks a Joe McCarthy: If you pushed your way into the inner sanctum of the Inner Party of progressivism, you would find not a cackling Kamala Harris, but an empty room.

For anyone on the wrong side of the new rules of thought and speech, though, the absence of a McCarthy figure is cold comfort. Whatever his corruptions, Viktor Orban might lose the next election, if the fractious opposition stays united. But where can you go to vote for a different ruling ideology in the interlocking American establishment, all its schools and professional guilds, its consolidated media and tech powers?

One answer, common to old-fashioned libertarians, is that you can't vote against cultural forces: You just have to fight the battle of ideas, at whatever disadvantage, with a Substack if your media colleagues force you out, or from suburban Texas if you feel uncomfortable in the groves of academe.

For others, though, this seems like a naïve form of cultural surrender: Like telling a purged screenwriter during the Hollywood Blacklist, "Hey, just go start your own movie studio." Which is part of how a figure like Orban becomes appealing to American conservatives. It's not just his anti-immigration stance or his moral traditionalism. It's that his interventions in Hungarian cultural life, the attacks on liberal academic centers and the spending on conservative ideological projects, are seen as examples of how political power might curb progressivism's influence.

Some version of this impulse is actually correct. It would be a good thing if American conservatives had more of a sense of how to weaken the influence of Silicon Valley or the Ivy League, and more cultural projects in which they wanted to invest both private energy and public money.

But the way this impulse has swiftly led conservatives to tolerate corruption, whether in their long-distance Hungarian romance or their marriage to Donald Trump, suggests a fundamental danger for cultural outsiders. When you have demand for an alternative to an oppressive-seeming ideological establishment, but relatively little capacity to build one, the easiest path often leads not toward renaissance, but grift.

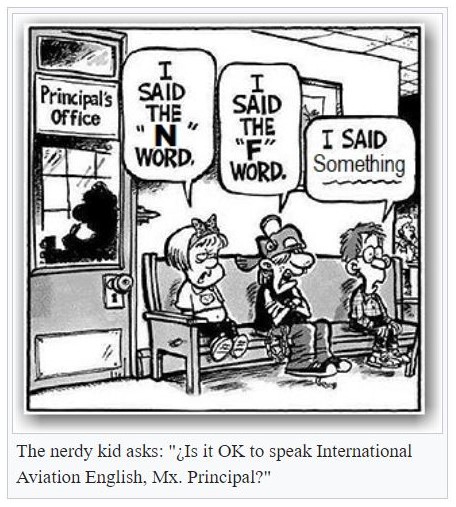

I do not want to be told what it is OK and what is not OK for me to THINK or speak. If people want to scrub language clean, that makes me want to speak dirty to rub their smiling faces in what I think of them, and to draw a line to keep them out of my First Amendment rights space.

I do not want to be told what it is OK and what is not OK for me to THINK or speak. If people want to scrub language clean, that makes me want to speak dirty to rub their smiling faces in what I think of them, and to draw a line to keep them out of my First Amendment rights space.

Everybody should be free to say whatever they damned well please, including blasphemy and obscenity, provided it is not acts of material violence effected thru words. A pink slip is an economic act, not a discursive act. For a military officer to command a rank of infantrymen: "Fire!" is an act violence, possibly an act of murder, not a discursive act. On the other hand, for a person to say something like: "I hate [the "N" word which I should write here but am too intimidated by them to do it]s" should be entirely acceptable, albeit it is "low brow" and "tacky". I just now thought of a new slur word: The "G" word, referring to all the people who have "gig" jobs: they are "giggers", aren't they? What could be more disgusting than to be a gigger?

Sticks and stones can break my bones but names cannot hurt me. l am a "Polack". if I was of African ancestry, I'd be a [the "N" word which I should write here but am too intimidated by them to do it]. What's the big f*cking deal, squeals?

People need to get off being goddamned "thin skinned" and stop being quick to take self-righteous offense at words, or at any image which does not encourage behavior which might entail the need for a person or animal needing medical attention. They need to just get over it (and get over thmselves, too)! What's their big goddamned problem? Give 'em a massive dose of Ex-Lax and lock them out of the loo.

The solution to the pornography problem is simple: Encourage healthy sexuality. Encourge everybody, including young children, to safely pleasure themselves (aka:"masturbate") when they can't have a loving partner with whom to have erotic pleasure, and teach them how to enjoy their bodies to the fullest capability of both their bodies and their souls.

Call out prigs and prudes and young women who play sick sex games like "look don't touch" as shameful, disgusting, despicable threats to public health and safety. Attractive females should dress modestly in public so as not to exacerbate the frustration of men who "aren't getting any". No ifs and or but[t]s. Period (←another double meaning word).

On CNN, a famous sportscaster (Bob Costas?) explained why professional athletic teams are changing their names from things like "The Redskins" which some people do not like. He said they are changing their names:

"not because they saw the light but because they felt the heat."

There are weeds which send out long tendrils that reach out to wrap themselves around anything they touch: grasping tendrils that will reach across a street or anywhere they can extend themselves to wrap their repulsive strand around it (ultimately choking it?). Sometimes something curious happens: Two tendrils touch each other, and, being entirely mindless, like the invisible hand of the capitalist market, they assume they have found a suitable destination and wrap themselves around each other, thus fulfiling their destiny while not hurting anything else.

Would that the prigs and prudes and other obnoxious people who are always trying to wrap their tendrils around everything always did the same. [During The Cold War, the acronym "MAD" meant "Mutual Assured Destruction", which would have been the outcome of a World War III between the United States and the Soviet Union.]

[Writing in Viktor Obrán's autocratic Hungary:] "He was sitting in a placid garden, enjoying a lemonade, wearing cargo shorts. 'This is maybe the strangest part,' he said, 'Even my parents, who lived under Stalin, still drank lemonade, still went swimming in the lake on a hot day, still fell in love. In the nightare scenario, you still have a life, even if you feel somewhat guilty about it.'" (Andrew Marantz, :Letter from Budapest: The Illiberal Order", The New Yorker, +2022.07.04, p. 45)

Just substitute "Dwight Eisenhower" or "Ronald Reagan" for "Stalin", and you have the world in which my parents lived – and I (BMcC[18-11-46-503]) was stuck in – here in The United States of America, where, as the old Ponderosa Steakhouse ad had it: "You dont't know how good it is, 'til you eat come place else." Siberia or Suburbia. They did not feel any guilt; I felt oppressed, but made the best of it and put the best face I could on it, and didn't feel the full malignancy of it....

People are sold a bill of goods how great it is in The U.S.A. and how bad it was in the U.S.S.R. But isn't that like saying having a headache is better than having a brain tumor? Stalin was running a country where the peasants had been Emancipated only a century before, whereas Eisenhower and Reagan were running the richest nation in the whole history of the world, and this after the great war that had been won on American arms and Russian bodies. He couldn't do better; We chose not to do better. A not insignificant difference.

Unfortunate for themself, the person who lacks one; unfortunate for others, the person that is one. Don't be an a**hole! |

|